“I drove my bike into the yard and park it under the old tree next to our communal space. As expected everyone is busy. It’s the end of September, peak season in our community. During the last week, the whole community has been involved in the harvesting of the hop. The next days will be challenging: everyone is tired and when working that close, sometimes frustrations grow.

Five years ago we decided to ask for extra help during harvesting season. Normally we are a community of 13 people, most of them are families that immigrated some years ago. Now, we have 4 new temporal inhabitants.

Living together with 13 and sometimes 17 people means we also need social boundaries, rules and structure. These are not fixed and can change if they no longer benefit our community. I think that’s exactly what rules should be. They are beliefs you have in common, but shouldn’t dictate those who live there.”

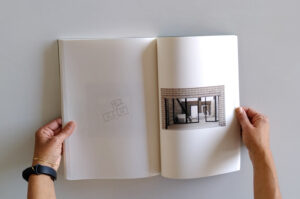

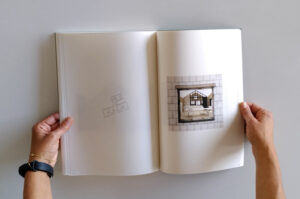

‘t Stalleke is a small shop where passers-by can take the products on display and pay a fair price for it. There is no supervision, only faith in goodwill. ‘t Stalleke suggests an exercise in trust. It’s a gesture from the farmer and community towards the outside world: “we trust you, you can try as well”.

‘t Stalleke is a small shop where passers-by can take the products on display and pay a fair price for it. There is no supervision, only faith in goodwill. ‘t Stalleke suggests an exercise in trust. It’s a gesture from the farmer and community towards the outside world: “we trust you, you can try as well”.

Astrid and Julia’s project look at ‘t Stalleke as a foundation for social relations in their community. Their project suggests that the architect cannot define the outcome, but only act as a mediator for such intention. The chance of succeeding mostly depends on the inhabitants, in their case a group of three to four refugee families. After approval to leave the asylum, immigrant families are often left to their fate. With no support from the government, and having no existing social network in a foreign country, it is almost impossible to find a proper house. It is also a established practice, in agriculture, that foreigners are temporary employed, if not exploited, as seasonal farmhands.

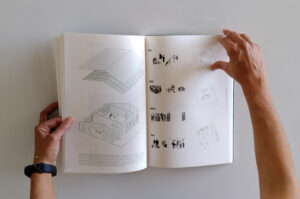

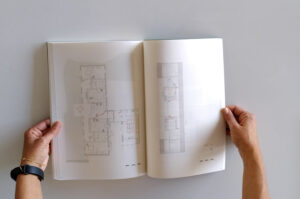

Astrid and Julia’s project seeks for an alternative to this condition by not only providing a house, but also by making foreigners part of a neighbourhood and farming company. Their envisioned community is located in an existing introverted old farmhouse that is retrofitted to become a communally shared farmhouse. This is located in a privileged site in the countryside, that is mostly populated by middle-class natives. While aware that this will cause frictions, mainly by the lack in communication and the general stereotyping that happens, their project aims to encourage engagement and participation through two main activities: bricolage and farming. These activities are vehicle of communication. Not only verbal, but also through gestures.

In restorative justice an approach is applied to conflict that differs from ‘conflict resolution’. Normally, the urgency to avoid and solve conflicts in in society leads to paths of exclusion and criminalisation in canonical justice. Restorative Justice is most importantly focused on communication between all the individuals directly or indirectly involved in the conflict. Since the lack of verbal communication is one of the main reasons why foreigners find it hard to participate in the civic life of Flemish society, Astrid and Julia are interested in the possibility for non-verbal communication.

In their project, the undefined rules of bricolage are used as a design methodology. Bricolage is much more than just an aesthetic choice: it is a necessary choice when economic resources are scarce, it lends itself to co-production, it can lead to achieve fast outputs while been opened and flexible to further development in the long term, and it makes use of waste materials. It suggests informality, spontaneity and solidity. Not accidentally, these three qualities that are also related to trust.

Trust means having clear but adjustable boundaries between all the playing actors. Far from advocating a boundary-free countryside – boundaries, they argue, are needed in trustworthy relationships and only becomes a problem when are obsessively used to give a false feeling of security – architecture is used in this project to articulate thresholds that are legible, yet can be negotiated as they materialise through layering and depth. This allows for openness and hospitality towards passers-by, while demarcating an inside from an outside.