“This is not a prison farm and this is not a true story. The event I am about to describe has no existence, so are the people involved. […]

These are thirteen people living and working together under the same roof. Their thoughts are hidden from me, so does the past they had and it will always remain like this. Before they started living on the Farm they might had been working as farmers, they might had no job at all, they might had been sent to prison or a mental health institution – it is not a matter of any importance. I am not saying that the past has no value but I see it as a very first layer usually built with no consciousness and knowledge. Some of them might had more wisdom, confidence or just a great luck in balancing and improvising at that stage but I can assure you that it has never been anyones’ plan to do something wrong.[…]

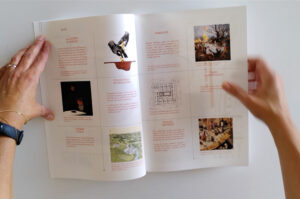

This huge portico – what a waste of space, of land that could have been cultivated, what was it made for? What has one to do here? Sit on the steps and light a cigarette in the shadow? Certainly it was a lovely spring morning, the weather was mild, the wind warm and there was no hardship in doing so. While he was sitting on the edge of a round shaped recession in the floor and lightning a good cigarette the sound of pigeon reached his ear. One of them sat and started drinking water from a round pond at the end of the arcade, then left its dropping on the ground and flew away.

[…]They built this pigeon tower together but firstly they had to demolish some parts of the glasshouse to open the sky for birds. For some of the thirteen this collective deconstruction was even more refreshing than building up the tower and brought the feeling of relief. After that for the first time they had a small gathering under the frontal arcades and they even invited some people from the village but nobody came.”

Monuments have the pretentiousness to shape the landscape of our values and therefore often become the subject of public disputes and can provoke conflicts. While often built to commemorate statesmen, heroes, and victims of wars, a deliberate tool of the authorities for constructing collective identity, over time they sometimes develop as the indifferent background of our life or, in particular situations, the material target of protests and anarchist resistance. These activities keep monuments alive.

While mostly an urban phenomenon, monuments are also in the countryside. Silos, chimneys, high voltage poles, and other technical structures are rural monuments accidentally representing the power of technology that serves daily life and production. They seem to reinforce the dogma that the countryside is a production site, a storage room for the city. Marta argues that the network of residential farms that she and her fellow propose, aims to recognise that the Flemish countryside is, and should be, much more than just the backyard of the city.

Marta’s project is a residential farm where humans and non-humans (pigeons) co-live. This is conceived as a growing monument which links past and present, work and leisure, conflict and celebration but also people and nature. She proposes to modify an existing and obsolete greenhouse by adding to it several monumental structures – arcades and pigeon towers – and by deconstructing the greenhouse to reveal some of its intrinsic monumental qualities. Collective deconstruction is both a ritual and a necessary building activity that allow for new uses and for a shared lifestyle between humans and non-humans. This collective monument is equally built by the newcomers – the thirteen residents of the farm and the pigeons – and the whole existing community of the village – the old owner of the farm in particular. To grow the monument, not only implies the design of new spatial forms: rituals such as taking care of pigeons, domestic duties, gatherings and celebrations, are non-material monuments itself.

The farm experiments with permaculture as a farming model and the community addresses the environmental predicament by stewarding self-sufficiency for their basic needs. Pigeons play significant role in organic farming by producing the fertiliser, but it does not mean that they just serve as a tool.

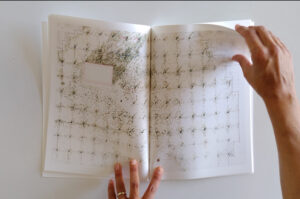

Living units for humans – bedrooms and bathrooms – are kept to a minimum and enclose fragments of the greenhouse’s grid: their expansion is allowed to gain more covered space inside the glasshouse, but at the condition that this remain a share space with non-humans.

Humans and non-humans remain equal users of the space. There are no labels and no exclusions.