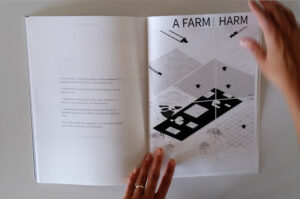

“Today I visited the site of a newly assigned project in Broechem. I immediately discovered some contradictions and conflicts of the countryside, that made my idyllic image of rural settlements dissapear. Greenhouses were scaled into factories for monoculture, and little remaining grass was plucked bare by animal husbandry. As I continued my walk, I noticed a number of neglected soils belonging to small farmers who cannot compete with multinational firms anymore. Nowadays agricultural cultivation includes plowing of soils on which heavy machines leave their marks and continue to harm nature. […] If our identity is a reflection of our living environment, I may assume that by harming nature, we are harming ourselves.”

Febe proposes to foster a community focused on tackling the issue of self-harm, which is a condition that touches a great number of people susceptible to drug abuse, eating disorders, self-inflicted violence, etc. In an original conceptual leap, Febe links this topic to environmental damage, arguing that this is also a form of self-harm. While distancing itself from arguments that understand architecture – and its final artefact – as a healing machine, Farm beyond harm supports a healing process aligned with principles of Environmental Restorative Justice.

The actual construction of the farm – which in her case includes the retrofitting of the existing glasshouse, the construction of new volumes, and the conversion of farmland to a new model of agriculture – is a process of creating a community and challenging the way in which individuals treat themselves, treat others, and treat the environment they depend on.

“On my way out, I took a last glimpse at the greenhouse. It’s undergoing evolution of the past 4 years flashed me by. I remembered the previously clay mountains that we used to bake the bricks. I remembered the first grain harvest, which allowed us to built the straw furniture for the sleeping units. I remembered one of the members, guiding me towards his individual storage unit to collect some grains for baking our bread. And I will remember the greenhouse, as a continously evolving project that is and never will be finished..”

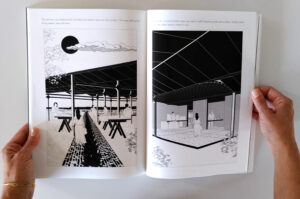

In the fields outside the glasshouse, she proposes a model of companion cropping, mixing cereals and leguminous plants, to regenerate the soil over time. Within the glasshouse, the farm members incrementally build housing: they first temporarily inhabit an existing shed, and gradually add new volumes. The new constructions make use of existing sources of materials that Febe has identified onsite to avoid the need for industrially-produced construction materials: making use of an existing pile of clay to make bricks, reusing steel frames from the glasshouse, or using broken glass to make terrazzo flooring.

The form of the housing is divided neatly along three human needs:

1. biological needs: sleeping, bathing occur in a mat-building, which has a modular structure and can shift with changing needs of individuals and families. This is built on top of the existing glasshouse.

2. convivial needs: underneath this structure is a space of convivial activity, where bread is baked, meals are prepared and individuals eat together.

3. the third need is otium: leisure time dedicated to intellectual or spiritual pursuits. This occurs out in the fields. 13 grain silos are not just used for storage but for individuals to escape collective life and relax.

“I needed to clear my mind for a moment and take some time for myself. Seeking refuge in this cold and dark space, surrounded by nature, where my external stimuli are suppressed. It all became clear to me, how this time, how this space, is intended to be alone.”